This website is dedicated to my father, Harry Dunegan.

Fishing with Dad during the Great Depression

Harry Dunegan, my father, was the first, average-person, conservationist aka environmentalist, I ever met. Born in the coal-mining town of Clymer, Pennsylvania, he was an eye-witness to the destructive nature of coal-producing operations. Irish Catholic and an avid outdoorsman, he loved fishing and hiking the hills, mountains and streams of Appalachia. More than once I saw him grieve the loss of a pristine trout stream to acid, orange mining pollution.

Fishing with Dad during the Great Depression

Harry Dunegan, my father, was the first, average-person, conservationist aka environmentalist, I ever met. Born in the coal-mining town of Clymer, Pennsylvania, he was an eye-witness to the destructive nature of coal-producing operations. Irish Catholic and an avid outdoorsman, he loved fishing and hiking the hills, mountains and streams of Appalachia. More than once I saw him grieve the loss of a pristine trout stream to acid, orange mining pollution.

At our home in Chattanooga, TN, he used every opportunity to teach about the environment. Formally educated as a ceramic engineer, he had a scientific mind and a deep passion for nature. He became a self-taught naturalist, studying botany, herpetology, and ichthyology, as well as soil conservation. He converted the basement of our home into a breeding center for freshwater native and tropical fish, and created one of the first collections of salt water fish to exist in the Chattanooga area. At any given time during the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, our basement housed an impressive number of turtles, salamanders, snakes and other reptiles. He kept them all in pristine aquariums with naturalistic environments.

In the early days of aquarium-keeping, electric lights, chemicals and air compressors were not used. The true naturalist established mini-ecosystems within the tanks, maintaining a precise balance between water quality, aquatic plants, scavenger species and fish. Dad’s aquatic displays reflected those unique skills. His practice was to collect a specimen, house it for a time so that we and interested others could study it, and then release it back into the wild.

Our basement aquarium was open to anyone at no charge. Children and adults spent hours there, fascinated by glimpses into underwater worlds. Crayfish, mud puppies, seahorses, even piranhas graced the tanks of Dad’s assemblage well before the widespread existence of public aquariums. His “hobby” enabled average people to experience rarely seen aquatic life. Visitors left our home with a deeper understanding and a greater appreciation for nature.

Field trips also expanded our knowledge. On hot summer days Dad would collect the neighborhood children and any interested adults who wanted to tag along. Then he would gather up his seines, (a type of net), and transport us by Jeep or boat to a slew, creek or stream to sample its health. He explained the concept of food chains, identified wild foods and rare plants, and showed us how to assess the health of a stream. Using the nets we would seine an area of the stream and count the number of vertebrates and invertebrates we found living there. While sampling he taught us the names of minnows, darters, and a host of other creatures we discovered hiding under the wet rocks. Sadly, few streams today yield the abundant variety of aquatic life a single dip of the seine could produce in those years

Fishing in Appalachia

Recognized locally as an expert, his skills were sought by the Tennessee Game and Fish Commission, where he regularly volunteered his services. He set up and maintained the native fish displays at the county fair each year and assisted at educational programs the Commission sponsored. Always willing to share his knowledge, Dad remained available to answer any and all questions, even if visitors remained until the wee hours of the morning.

Fishing in Appalachia

Recognized locally as an expert, his skills were sought by the Tennessee Game and Fish Commission, where he regularly volunteered his services. He set up and maintained the native fish displays at the county fair each year and assisted at educational programs the Commission sponsored. Always willing to share his knowledge, Dad remained available to answer any and all questions, even if visitors remained until the wee hours of the morning.

My father was responsible for the health and safety of the giant, four-foot catfish on display during fair week. He opposed the dry handling of fish, and pioneered catch-and-release practices by teaching wet-handed techniques for handling fish to protect their slime layers. This insured the health of the fish and prevented the post-release development of fungus. He would then supervise the release of the giant catfish back into the Tennessee River.

His interests also included soil conservation and he was an early supporter of recycling. He taught us the about trees and conducted tree planting expeditions when hundreds of trees were planted to prevent erosion. He also taught us how to sort metals, and encouraged the recycling of metal, paper and glass years before the advent of Earth Day.

My father taught me that standing up for the environment was not always easy. He funded and conducted a breeding project to reintroduce Bobwhite quail into an area that had been over-hunted. His project ended abruptly when a vandal took a shotgun and killed hundreds of birds. His entire breeding stock was destroyed, as well as cages and equipment, while the quail sat helplessly inside.

Once while traveling late at night through uninhabited parts of the Tennessee mountains, we saw a fire burning in the depth of the forest. Concerned about the possibility of a forest fire, Dad sought out the mouth of an old fire trail and followed it back to the fire. There he discovered a stolen car that had been stripped and set ablaze. He cleared nearby brush from the area and stayed watching the fire until it was no longer a threat to the woodland.

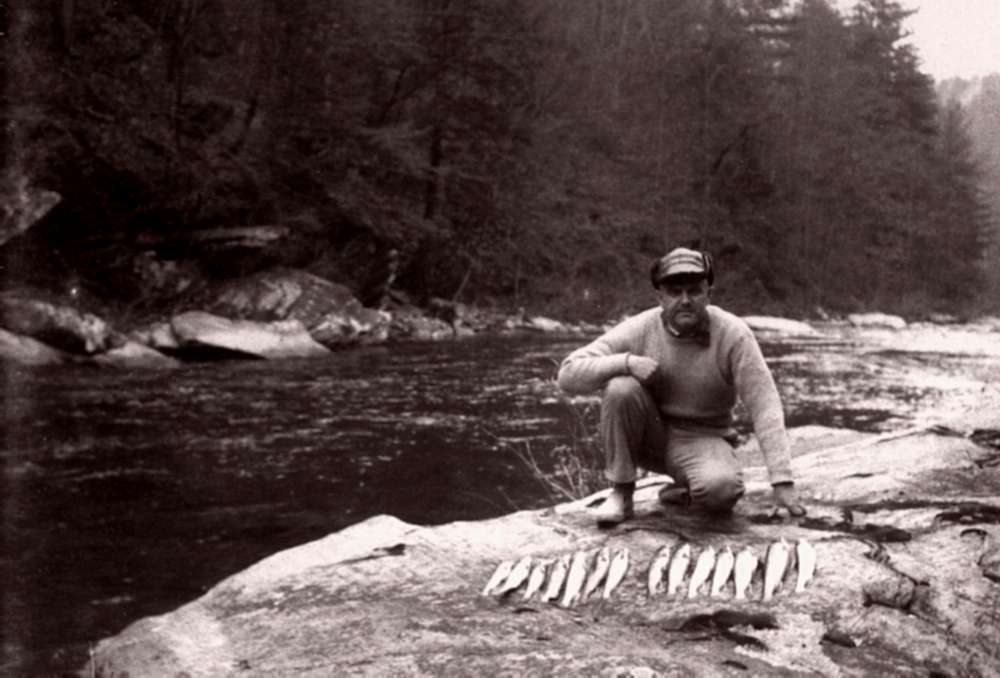

A day’s trout fishing for Friday night fish fry. In later years, Mr. Dunegan would become an early supporter of catch and release practices, always reminding fisherpersons, “Never touch a fish with dry hands!” He also purchased fingerling trout and restocked over-fished streams using his own funds, living out the conservationist motto, “Replace what you take.”.

He worked with school children on science projects to test ways to neutralize acid mine drainage. He purchased fingerling trout and restocked over fished trout streams. But my most instructive memory came on a day when one of our neighbors, surrounded by a group of young children, was showing a boy how to shoot woodpeckers with a BB gun. The man had just shot a bird, and was displaying the wounded creature to the children, when Dad arrived. He confronted the neighbor with what he had done.

A day’s trout fishing for Friday night fish fry. In later years, Mr. Dunegan would become an early supporter of catch and release practices, always reminding fisherpersons, “Never touch a fish with dry hands!” He also purchased fingerling trout and restocked over-fished streams using his own funds, living out the conservationist motto, “Replace what you take.”.

He worked with school children on science projects to test ways to neutralize acid mine drainage. He purchased fingerling trout and restocked over fished trout streams. But my most instructive memory came on a day when one of our neighbors, surrounded by a group of young children, was showing a boy how to shoot woodpeckers with a BB gun. The man had just shot a bird, and was displaying the wounded creature to the children, when Dad arrived. He confronted the neighbor with what he had done.

“This is a rare bird, and there are not many left,” he said. “You should not be teaching these children to kill woodpeckers. Instead, you should be trying to save them.”

I felt the cruelty of the man’s laughter as he mocked my father’s efforts to save the dying bird, for I was one of those watching children. Yet as children can, I sensed the weakness behind the destructive act. At that moment, I realized that I had a choice. I could grow up to be like the man who killed woodpeckers, or I could grow up to be like my father. I knew no one else who had wonderful and interesting things like fish, snakes and turtles living in their basement. No one else could keep giant catfish alive and return them to the river, instead of frying them up for a meal. That day I realized that not everyone sees nature as something beautiful to be cherished and protected. With the senseless death of that magnificent bird, and the cruel man’s laughter echoing in my ears, I knew that it would not be easy to grow up to be like Dad. But somehow I knew I’d have to try.

Thank you, Harry Dunegan. Your life stands as a testimony to the great good an average man of courage and conviction can quietly accomplish. This organization and website are respectfully dedicated to you, because without your influence and example, they would not be here.